Background

Common signals of previous library book use include mutilation and maginalia; their presence can lead to the removal of the book from the library’s collection. Mutilation is the preferred terminology for describing library books with broken spines; folded, ripped or removed pages; underlining, highlighting, and annotation of text (marginalia); and stains caused by food or drink (Higgins 2015). Such destruction is likely the result of need rather than maliciousness; patrons lack an understanding of library policy and practice, stealing or damaging library books in an effort to complete research and school assignments. To eliminate this seemingly deviant patron behavior, library workers are encouraged to provide orientations on how to properly use libraries, inform patrons of replacement costs, increase the number of security staff, and restrict access to certain material (Fasola and Oyadeyi 2019; Smith and Olszak 2011; Pedersen 1990). However, rectifying such behavior reinforces the panopticon concept of libraries (Radford, Radford, and Lingel 2018). Notably, a majority of students who admitted to stealing library books “agreed that the library was cold and anonymous” (Pedersen 1990, 126-7). As library staff focus on enforcing policy and procedure, patrons are continually reminded “that library space is dominated by surveillance and order” (Radford, Radford, and Lingel 2018, 685).

When a future reader encounters a past reader’s annotations, the book “turns into an interactive act of handing down information from one reader to the next one in line”

Marginalia, including underlining, highlighting, and annotating text, is well examined in the literature. Contrary to the “mutilation” nomenclature of librarians, Bjorneborn and Fajkovic (2014) found that 40% of patrons appreciate marked-up library books noting, “they can comprehend the text more easily because of the comments and annotations made by previous readers” (911). Six functions of such reader commentary by students have been identified by Marshall (1997): as procedural signals identifying the important portions of a text in relation to an assignment; as placemarks for critical text to quote or return to; as ways of working through problems; as a means of interpreting the author’s words or the annotation of another student; as a method of visibly tracing their progress through the text; and as incidental markings, such as doodles, that are unrelated to the text. Attenborough (2011) found similar results, identifying marginalia by students as “pedagogic aids” (103) in which anonymity “undoubtedly played a part in enabling these publicly observable displays of ‘doing education’” (109). When a future reader encounters a past reader’s annotations, the book “turns into an interactive act of handing down information from one reader to the next one in line” (Bjorneborn and Fajkovic 2014, 904).

Sometimes the author of marginalia is known and, consequently, the side commentary is treated as a significant added value. Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s marginal note-taking is well-documented by H.J. Jackson (2001). In an early essay, Jackson (1993) relays a conversation with a librarian after he had identified Coleridge’s commentary in two of the library’s books. This increased the market value of the books, likely worth more than the librarian’s salary. The librarian’s response to this news? “People aren’t supposed to write in our books” (Jackson 1993, 217). She saw no difference between the poet and ordinary readers who dare leave behind a trace of their scholarly inquiry. A web project from the University of Virginia, Book Traces documents 19th and 20th century texts that “bear marks of use by their original owners;” viewers can browse an individual’s book use through images capturing “marginalia, annotations, inscriptions, and insertions” (“About”).

What if librarians acknowledged these remainders of use as traces of scholarly communication, rather than destruction?

The paradox of marginalia is again prevalent as library collections shift from print to electronic books. Students are discouraged from writing in print books while online participatory culture promotes tagging, commenting, and other forms of annotation in digital texts. In discussing the transition of marginalia from the printed page to the electronic one, Wagstaff (2012) comments “we are reinventing the same ideas, in a digital format, because they serve the same basic human desires” (22).

What if librarians acknowledged these remainders of use as traces of scholarly communication, rather than destruction? How might we consider print collections as a means of connecting people to people, rather than to static information? Dourish and Chalmers (1994) theorize that “selecting objects because others have been examining them” is a form of social navigation. This community of readers is what makes a library’s copy of a book different from your store-bought copy. “Without seeking direct social contact, people still follow others as a means of discovery and inspiration” (Johansson 2014, 19).

Several artist works document reader engagement with one another through an emphasis on mutilation and marginalia. One project that encourages readers to leave traces of their navigation is Open Edit (2011), a mobile library that brought the Asia Art Archive to different Asian cities. The public was welcome to mark up the books through marginal writing, highlighting, and even removing pages. The Asia Art Archive states, “through these actions, people are reinterpreting the material, as well as engaging in a dialogue amongst themselves.” A photographic work that emphasizes book destruction from use is Kerry Mansfield’s Expired (2017). The series documents library books that have been withdrawn due to overuse, a “tactile decay reflecting a collective act of reading” (Meier 2017).

Individual texts have also become artistic inspiration, questioning library authority for determining a book’s shelf life. In A Room of One’s Own / A Thousand Libraries, artist Kajsa Dahlberg (2006) created a new version of Virginia Woolf ’s A Room of One’s Own (1929). This book includes all of the marginalia found in Swedish library copies of the text. Dahlberg states that she found herself “concentrating, not on the text itself, but on that space which is not the text” (Crone and Towheed 2011, 124). The space that is not text is the space within which readers communicate with the author and with one another. Another artist, John Latham, took library book use to the extreme. In 1966, he checked out the St. Martin’s School of Art’s library copy of Clement Greenberg’s Art and Culture (1965). He and his students chewed the pages of the books, then fermented the paper paste in jars. When he began receiving overdue notices from the library, Latham attempted to return the book in its new form. The work was rejected by the library and Latham lost his teaching job at the college. The work is now in the Museum of Modern Art (Pisciotta 2016; Mellby 2009).

Alternative Art History

While working on this project, I repeatedly thought of two books each from a different library where I’ve worked. One was a music literature text that had never been borrowed. When I looked at the book for withdrawal, I found a note from two former students. They had met and fallen in love at this university; they returned annually and left a note to their future selves in this text. Eventually, they returned with their two children, writing a marginal note each year. The book’s text had no value, as evidenced by its lack of scholarly use. But the book, tucked away on a corner shelf in the music reading room, was priceless to two, and now four, people. I placed it back on the shelf.

We might say, our priority is future readers, but the most efficient method of preserving our materials is to have no readers at all. In Alternative Art History, only the readers are preserved.

Another book, an art history text, also contained notes from former students. At some point, a student had written a note to future readers explaining the teaching methodology and grading of a particular faculty member. Over time, other students contributed their own personal experiences with this faculty. They were kind, reassuring current students that this, too, shall pass.

Alternative Art History examines readers engagement with one another through print text. Imagine the librarian has been ordered to weed print material as it is taking up space needed for an augmented reality lab. These books have no digital surrogate; when the books are withdrawn, the scholarship will also be gone from that library. We say our priority is our patrons but our policies and procedures are for the benefit of the book. We might say, our priority if future readers, but the most efficient method of preserving our materials is to have no readers at all.

In Alternative Art History, only the readers are preserved. To save their scholarly conversation, the librarian keeps only text that had been considered important to past readers. Social navigation is evident in these books’ pages. Once a book has been edited by a user, future users build on those edits, evidenced by highlighted text that is also underlined, highlighted again, or commented on in the margins. These navigations determine what information in the book is most valuable. The underlining, highlighting, and annotation become the new art history textbook.

Bibliography

“About.” 2021. Book Traces. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://booktraces-public.lib.virginia.edu/about.

Attenborough, Frederick Thomas. “‘I Don’t F***ing Care!’ Marginalia and the (Textual) Negotiation of an Academic Identity by University Students.” Discourse & Communication 5 (2): 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481310395447.

Björneborn, Lennart, and Muhamed Fajkovic. “Marginalia as Message: Affordances for Reader-to-Reader Communication.” Journal of Documentation 70 (5): 902-26. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-07-2013-0096.

Crone, Rosalind, and Shafquat Towheed. “A Book of One’s Own: Examples of Library Book Marginalia.” In The History of Reading: Methods, Strategies, Tactics, 115-131. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Dahlberg, Kajsa. 2006. “A Room of One’s Own / A Thousand Libraries.” Accessed November 21, 2020, http://www.kajsadahlberg.com/work/a-room-of-ones-own–a-thousand-libraries/.

Fasola, Omobolanale Seri, and Oyadeyi, Adekunle Emmanuel. 2019. “Deviant Behaviour Among Users of Academic Libraries: A Study of Two Academic Libraries in Oyo State, Nigeria.” Library Philosophy and Practice 2504: 1-16. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2504/.

Higgins, Silke P. 2015. “Theft and Vandalism of Books, Manuscripts, and Related Materials in Public and Academic Libraries, Archives, and Special Collections.” Library Philosophy and Practice 1256: 1-23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1256/.

Jackson, H.J. 2001. Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Jackson, H.J. 1993. “Writing in Books and Other Marginal Activities.” University of Toronto Quarterly 62 (2): 217–31. https://doi.org/10.3138/utq.62.2.217.

Johansson, Siri. 2014. “BookNode - Tactics for the Library in the Augmented City.” Thesis, Umea Institute of Design. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-91612.

Mansfield, Kerry. 2017. Expired. San Francisco: Modernbook Editions.

Marshall, Catherine C. “Annotation: From Paper Books to the Digital Library.” Paper presented at the Second ACM International Conference on Digital Libraries, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, July 1997. https://doi.org/10.1145/263690.263806.

Meier, Allison. “Loved to Death: A Photographer’s Tribute to Discarded Library Books.” Books (blog). Hyperallergic, October 24, 2017. https://hyperallergic.com/403659/loved-to-death-a-photographers-tribute-to-discarded-library-books/.

Mellby, Julie L. “The Man Who Ate ‘Art and Culture’.” Graphic Arts (blog). Princeton University Library, March 24, 2009. https://www.princeton.edu/~graphicarts/2009/03/the_man_who_ate_art_and_cultur.html.

Pedersen, Terri L. 1990. “Theft and Mutilation of Library Materials.” College & Research Libraries 51 (2): 120–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0176-7_11.

Pisciotta, Henry. 2016. “The Library in Art’s Crosshairs.” Art Documentation: Bulletin of the Art Libraries Society of North America 35 (1): 2-26. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/685974.

Radford, Gary Paul, Marie Louise Radford, and Jessa Lingel. “Transformative Spaces: The Library as Panopticon.” Paper presented at the Transforming Digital Worlds, Sheffield, UK, March 2018. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-78105-1_79.

Sàn Art. 2011. “Open Edit: AAA Mobile Library.” Accessed November 21, 2020, http://san-art.org/exhibition/mobile-library/.

Smith, Elizabeth H., and Lydia Olszak. 2011. “Treatment of Mutilated Art Books: A Survey of Academic ARL Institutions.” Library Resources & Technical Services 41 (1): 7–16. https://doi.org/10.5860/lrts.41n1.7.

Wagstaff, Kiri L. 2012. “The Evolution of Marginalia.” Paper, San Jose State University. https://www.wkiri.com/slis/wagstaff-libr200-marginalia-1col.pdf.

Page 444 (left). Reading American Art

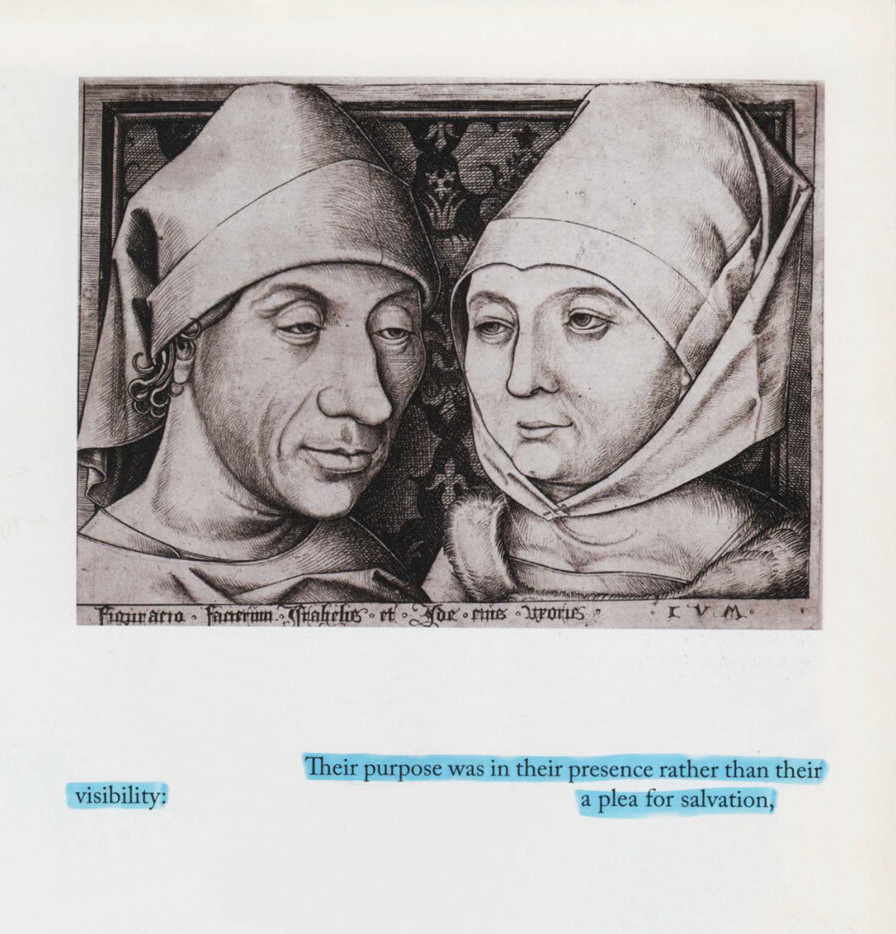

Page 444 (left). Reading American Art  Page 38. Alternative Art History

Page 38. Alternative Art History