Background

Library staff continually work to make books easier for patrons to locate. This is admirable, but we must acknowledge the underlying authority in doing so. “Librarians classify, catalog, index, and arrange all of the discourse under their jurisdiction… the power of the library’s classification scheme is massive and total” (Radford and Radford 2001, 305). Patrons are keenly aware that when they retrieve books from the stacks, disorder begins. Control is so powerful that they are expressly told not to return books to the shelves. Cheinman (2014) suggests that patrons will often hesitate to pull a book from an orderly shelf, noting “mild disarray provides comfort, and it seems to communicate to the visitors that someone else prior to them had engaged with this material” (45). Indications of previous patrons in the stacks encourages library book use.

While a few libraries have made modifications to traditional library classification systems, “library classification is often not driven by quality or appropriateness to collection, but rather by a form of inertia. The same systems are used because they have always been used” (Clarke 2013, 227). Artists and designers frequently adopt this inertia as inspiration. An early speculative project related to library catalogs employed scent as a search strategy. In the early 1970s, the Upper Arlington public library in Ohio created the “Stick Your Nose in the Card Catalogue” project (“Fragrance-coded Card Catalog” 2018). Scratch-and-sniff scents were added to the card catalog so patrons could find a book by smell, sniffing along the stacks to find the book on the shelf that matched the card’s scent. While sniffing their way to a book can be viewed as a fun experiment, it required patrons to engage with the catalog and stacks in an entirely new way, reinventing the physical and social connections created by library spaces.

In the early 1970s, the Upper Arlington Public Library in Ohio created the “Stick Your Nose in the Card Catalogue” project… An early speculative project related to library catalogs employing scent as a search strategy.

These social connections are also explored in Eva Eriksson’s (2013) iFloor. She notes that the use of personal technology in public libraries turns the shared space “into small bubbles of private spheres” (7). To encourage community interaction, iFloor is a floor where answers to patron questions are displayed. Similarly, for the Seattle Central Library, artist George Legrady (2003) installed screens that displayed information about recently borrowed material, making community action visible (Pisciotta 2016). Siri Johansson’s (2014) thesis, Book Node, also prompts engagement by building on the participatory culture of libraries and examining a book’s use by multiple patrons over time. The project includes city nodes, places around the city where electronic books can be borrowed, returned, and recommended, and a library hub that provides digital connections between patrons reading print books. Ultimately, Book Node “comes very close to the previously unintended function of the book card with stamps and signatures, of giving a sense of connection to former readers and a bit of story about the book’s past” (Johansson 2014, 36).

Alternative cataloging projects also question the authority of library classification schemes. For a New Jersey public library, Michael Clegg and Martin Guttmann (1990) cataloged books by their color and then created an artist book as “a bibliography that seems to intentionally assign Dewey Classification numbers incorrectly” (Pisciotta 2016, 12). The Prelinger Library’s books are shelved geospatially, rather than by traditional classification. “This arrangement system classifies subjects spatially and conceptually beginning with the physical world, moving into representation and culture, and ending with abstractions of society and theory” (“Collection: The Library’s Organizational System” 2020). These new classification systems create new connections between books, and subsequently between readers.

Hair Catalog

Hair Catalog is another attempt to connect readers to readers. In the future, print books will not be valued for their text and image content, which may likely be available online, but as remnants of the past. As library collections become dominated by ebooks there are certainly electronic traces of past readers, but they are often not visible to current readers. Even if personally identifying information is available, there is a digital distance between readers that suggests anonymity and isolation. In aging print collections, future library users will seek this network of humans who handled and engaged with the book as an object.

As library collections become dominated by ebooks there are certainly electronic traces of past readers, but they are often not visible to current readers.

Dourish and Chalmers (1994) theorize that “selecting objects because others have been examining them” is a form of social navigation (1). This community of readers is what makes a library’s copy of a book different from a store-bought copy. “Without seeking direct social contact, people still follow others as a means of discovery and inspiration” (Johansson 2014, 19). Hair Catalog considers what future questions we might be able to answer about past readers and their interests. The project also raises concerns about what conclusions we might make using quantitative data or outdated methods of data collection and assessment.

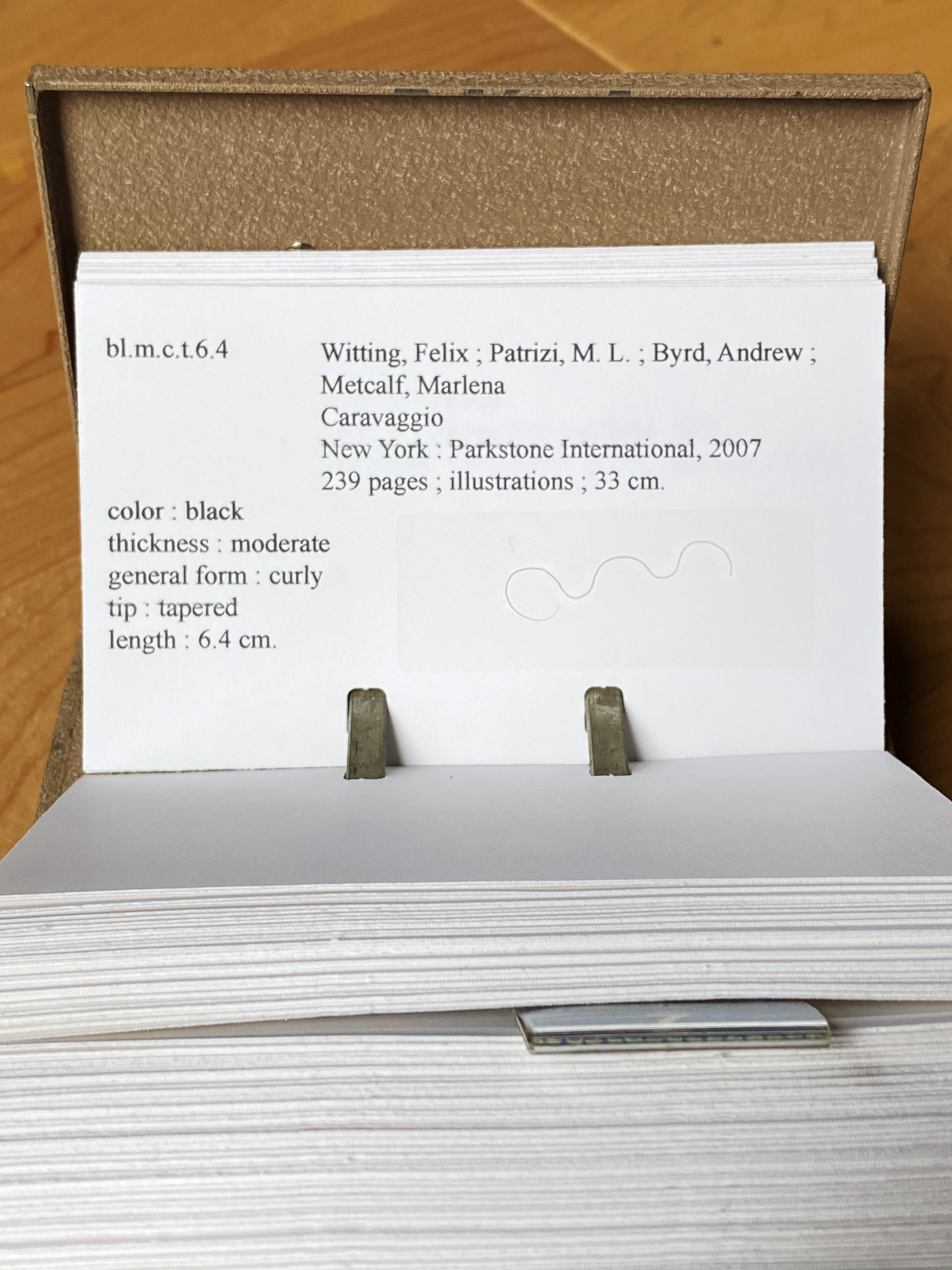

The estimated daily scalp hair loss is between 100-150 hairs, therefore the presence of hair in handled library books is highly expected. The distinct data fields for hair examination used for this catalog were derived from James Robertson’s (1999) Forensic Examination of Hair. Robertson’s book was the first to bring together experts providing a comprehensive overview of the discipline, yet forensic examination of human hair has greatly changed in the past twenty years and is fraught with systemic biases about race, ethnicity, and age. I opted to use this outdated system to catalog my samples to help me reflect on issues with classification and cataloging. The book provides general categories of hair attributes to examine including length, thickness, color, and tip. Each attribute, except length, has a set of options to select from and each hair was best matched against those options. For example, a hair’s tip could be classed as tapered, cut, frayed, or split. General form could be straight, wavy, or curly.

The hairs were collected at an institutional library where I once worked. While examining books for withdrawal, I flipped through the pages to understand subject matter, image quality, and condition. Given my subject expertise in art, most of the books are about fine arts. When a hair was found between the pages, I taped it to paper and noted the book title. Each book’s attributes for Hair Catalog are from WorldCat metadata; the entire collection can be accessed as a WorldCat public list. Determinations of hair attributes were set against the author’s own hair - straight, fine, brown hair - meaning that the entire process of cataloging was subjective. As an example, a fine, straight brown hair with a tapered tip and 5.4cm in length found in Kenneth Clark’s Masterpieces of Fifty Centuries has the Hair Catalog call number br.f.s.t.5.4.

In Hair Catalog, the call number is derived from Robertson’s attributes. This project falls within associative design by asking viewers to use their “familiarity with form, typology, and design language” (Malpass 2013, 337). Instead of traditional metadata of a library book, such as title and author, Hair Catalog uses metadata of forensic examination. While the metadata schema is unfamiliar, the process of identifying attributes to describe an object is understood. The Catalog consists of two hundred human hair samples. While I had more than two hundred samples, the decision was made to cap the project and begin analysis. Here, too, there is subjectivity in acquisition as I selected hairs from my total collection that appeared unique and contained ample information. To diversify the collection, hairs other than a shade of brown were prized, especially those of a reddish hue. Curly and coarse hairs were also rare and therefore valued. Of the two hundred hair samples, three were lost in processing. Three samples were broken during cataloging; one of these was repaired. Two samples were already damaged by knots and only three included the hair root. Another three were identified as animal hair and, along with one paint brush bristle, set aside for special collections.

A Rolodex model V535 is used to house the card catalog. Rolodex, first introduced in the mid-twentieth century, was intended to keep contact information of business associates, friends, and family on alphabetically-filed index cards. The use of a Rolodex for a hair catalog, a collection of anonymous persons, is intentional. Coincidentally, this purchased Rolodex was originally someone else’s library catalog, demonstrating the commonalities between filing metadata for people and books. Their collection includes titles such as Elementary Engineering Thermodynamics, Practical Taxidermy, Prince Valiant and the Golden Princess, and Twenty-five Vegetables Anyone Can Grow. They also cataloged an autographed copy of Terry’s Hunters.

Forty-five percent of samples are of moderate thickness, followed by 41% fine and only 14% coarse. Most of the coarse hairs are black. All white hairs and almost all yellow hairs were fine. A majority of the collection are straight samples, at 69%, with 22% wavy, and 9% curly. Overall, people take good care of their hair; almost half (49%) of tips were cut, 41% tapered, with only marginal damage by fraying (3%) or split ends (7%).

The subjects of the books vary, but are dominated by American or Italian art and artists. Those with black hair were interested in Italian art while those with brown or yellow hair preferred American art. People with short hair favored books on abstract expressionism. Mostly those with straight hair used books on Chinese art or artists. People with moderately thick hair selected books on Caravaggio while books about Pablo Picasso were only used by straight-haired people. Only people with brown hair read books on Japanese art and they did not read anything about architecture.

People with moderately thick hair selected books on Caravaggio while books about Pablo Picasso were only used by straight-haired people.

Books 29cm or shorter in height had an average shorter hair length (6cm) than books 30cm or taller (10.3cm). People with yellow or brown hair read longer books (270 pages average) than black-haired people, reading books averaged 245 pages in length. White or red-haired people read less (225 and 213 average page length). Curly-haired people read more recent publications (1994) than straight (1987) or wavy (1989).

Marilyn Stokstad’s All About Art: An Essential History was used by someone with black coarse hair and someone with dark yellow fine hair. Automatic Cities: The Architectural Imaginary in Contemporary Art was also used by people with black coarse and yellow fine hairs. Is the person with black coarse straight hair at 0.9cm length who read Automatic Cities: The Architectural Imaginary in Contemporary Art the same as the person with black coarse straight hair at 0.9 cm who read Artistic Expression: A Sociological Analysis?

Was the person reading Calder’s Universe who lost at least three hairs, two with the roots, stressed or sick? Or Witting’s Caravaggio? Overall, Caravaggio books have a lot of hair; this suggests intimate reading. Picasso by Elgar and Maillard had at least four different people lose hair between the pages. It’s one of the smaller books in height, but relatively weighty in pages. It would take time to skim, let alone read in depth, suggesting that the longer spent with a book, the more likely hair would drift into the pages. Hair falling from a reader while lingering over a page spread, deeply gazing at an image. Flipping through these books’ pages, looking for evidence of use, of people, is seemingly nostalgic in a pandemic era. Preserve the reader.

Bibliography

Cheinman, Ksenia. 2014. “Creating Alternative Libraries.” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 33 (1): 41-58. https://doi.org/10.1086/675705.

Clarke, Rachael Ivy. (2013). “Color by Numbers: An Exploration of the Use of Color as Classification Notation.” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 32 (2): 222-38. https://doi.org/10.1086/673514.

“Collection: The Library’s Organizational System.” 2020. Prelinger Library. Accessed November 28, 2020, http://www.prelingerlibrary.org/home/collection/.

Dourish, Paul, and Matthew Chalmers. “Running Out of Space: Models of Information Navigation.” Paper presented at the British Computer Society Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Glasgow, Scotland, August 1994. http://www.dcs.gla.ac.uk/~matthew/papers/hci94.pdf.

Eriksson, Eva. “Intertwine and Play: Techniques and Tools for Multi-scaled Interaction Design - Experiences from Public Library Space.” Thesis, Chalmers University, 2013. https://research.chalmers.se/publication/174220.

“Fragrance-coded Card Catalog.” 2018. Weird Universe (blog), January 16, 2018. http://www.weirduniverse.net/blog/comments/fragrance_coded_card_catalog.

Johansson, Siri. “BookNode - Tactics for the Library in the Augmented City/” Thesis, Umea Institute of Design, 2014. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-91612.

Malpass, Matt. “Between Wit and Reason: Defining Associative, Speculative, and Critical Design in Practice.” Design and Culture 5 (3): 333-56. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2752/175470813X13705953612200.

Pisciotta, Henry. “The Library in Art’s Crosshairs.” Art Documentation: Bulletin of the Art Libraries Society of North America 35 (1): 2-26. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/685974.

Radford, Gary P., and Marie L. Radford. 2001. “Libraries, Librarians, and the Discourse of Fear.” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 71 (3): 299-329. https://doi.org/10.1086/603283.

Robertson, James. 1999. Forensic Examination of Hair. London: Taylor & Francis.

Fig. 1 - Masterpieces of Fifty Centuries

Fig. 1 - Masterpieces of Fifty Centuries  Fig. 2 - Hair Catalog

Fig. 2 - Hair Catalog  Fig. 3 - Rolodex model V535 Catalog

Fig. 3 - Rolodex model V535 Catalog  Fig. 4 - Automatic Cities

Fig. 4 - Automatic Cities  Fig. 5 - Caravaggio

Fig. 5 - Caravaggio